Writing ping utility using POSIX sockets [C++]: Part 1

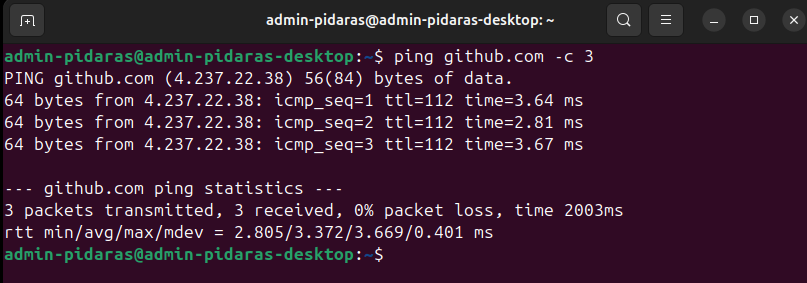

Everyone reading this article is likely familiar with ping utility:

Which is widely used as a simple way of verifying that certain host is online and capable of replying to requests (pings) from an outside network. This utility comes with most operating systems you can lay your hands on even if you're a Windows user, so it's fair to call it crossplatform.

A bit of history

Ping is a real O.G. when it comes to console utilities due to being around since 1983 (sic!) according to its source file:

* Author -

* Mike Muuss

* U. S. Army Ballistic Research Laboratory

* December, 1983Interestingly enough, it was developed by US Army Ballistic Research Lab (now part of The Army's Research Laboratory) which gives you an idea of how advanced network technologies were at that time in R&D departments of the US Army, long before Internet made its way to becoming widely used by general public in mid-late 1990s. Which is hardly a surprise to those familiar with other endeavours of the aforementioned laboratory:

Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) served as a major Army center for research and development in technologies related to weapon phenomena, armor, accelerator physics, and high-speed computing...

The laboratory is perhaps best known for commissioning the creation of the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC)...

Ballistic Research Laboratory's contribution to modern computer history can't be understated. Unfortunately BRL doesn't seem to get much recognition in this context, unlike our next big player whose name has also been mentioned in ping.c source file and is particularly (painfully?) familiar to Linux developers:

* Modified at Uc BerkeleyFamous Berkeley University (UCB) needs no introduction. It played major part in development of modern operating systems (and even hardware platforms), particularly those belonging to a realm of Linux. Things like BSD, Berkeley RISC, Vi (Vim's predecessor) and contributions to DARPA-funded research in a form of Project Genie are speaking for themselves. But there's one particular thing developed by Berkeley University that presents a lot of interest when it comes to network programming - the so-called Berkeley sockets, sometimes refered to as POSIX sockets, or BSD sockets. Which to this day happens to be one of the most crucial APIs in Unix-like operating systems.

This takes us straight to technical side of ping. How does it work? And what utility are we even writing here, for god's sake? - careful reader might ask. More on sockets later on, and for now - let's find out what the hell this article is even about.

Using ping on a range of hosts (aka subnet)

Let's go back to what we said at the beginning. Everyone here used ping at least once in their lifetime, right? But did you ever feel the need to ping multiple hosts from the same subnet at the same time? You didn't? Consider yourself lucky, which some of us aren't unfortunately.

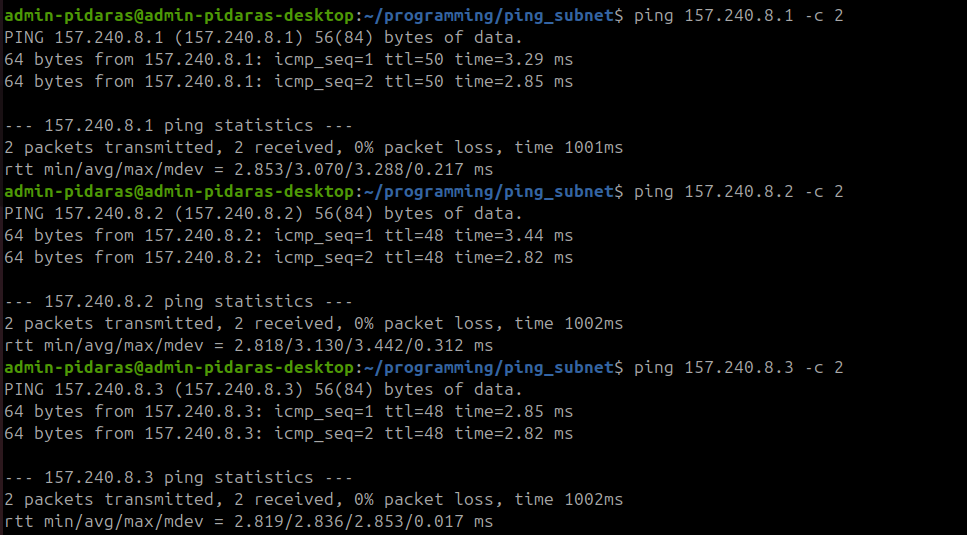

Having to ping three or four hosts wouldn't present a major headache - you could feed them one by one to one to ping and wait for result:

That's three or four. But what about thirty four? Or three hundred and thirty four? What if you need to ping all hosts from 8.8.0.0/20 subnet? Thats 4094 usable hosts to go through!

An experienced Linux user might say: "Just generate a list of hosts using your subnet-and-mask combo, put that in a text file and feed it to ping one line at a time using some convoluted Bash script. Make yourself a coffee while ping is traversing through your stupid list." Sounds like fun? Let's try that approach.

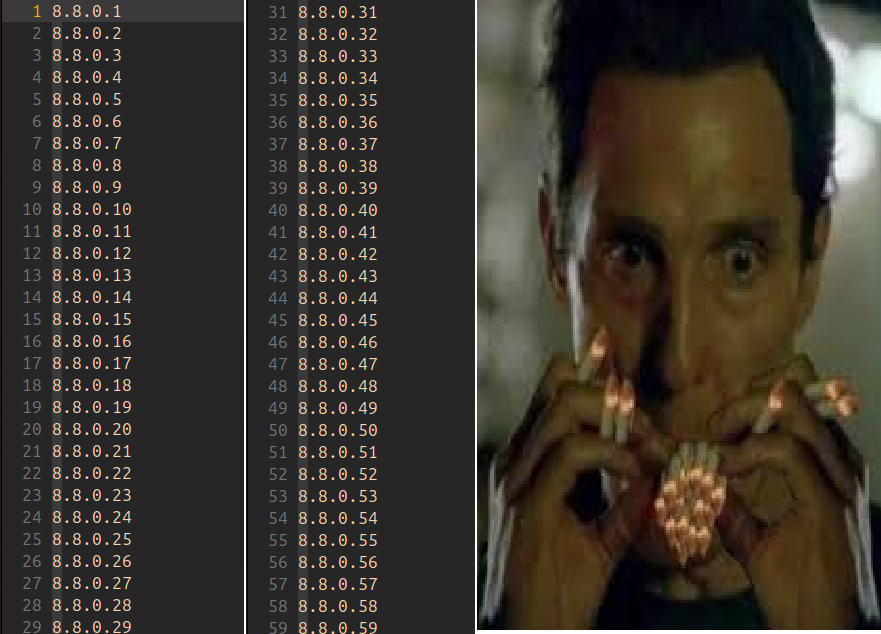

I created a file called hosts.txt which contains all the IP addresses from 8.8.0.0/20 subnet. First 59 entries of that file are shown in the picture above, but again, the file contains all 4094 IP addresses from the aforementioned subnet. Now let's write some crappy Bash script so we can feed all this crappily-structured data toping and finally find out whether any of those hosts are alive. For that I'll be using some shitty script I found on stackoverflow:

while IFS= read -r line; do

ping $line -c 1

done < hosts.txt

It's iterating through hosts.txt line by line (address by address) and feeding that to ping. We need to add '-c 1' argument in order to only send a single ping request for every host, otherwise ping will be stuck on the first address forever and your coffee will get cold.

So brace yourself while this software-engineering-masterpiece harassing 4094 hosts one at a time. New problem: for every offline host we'll have to wait 10 seconds before ping deems it unreachable. That's a default timeout used by ping. Only after 10 seconds will the script move to the next address. So what if three thousand hosts from our list are unreachable? Simple calculation:

3000 hosts x 10 seconds = 30000 secondsRidiculous! We're going to waste almost 9 hours all up just waiting for dead IPs to reply in a single run of this script. It's not even taking into account the rest of the hosts from that list. Not only will your coffee go cold, but you might also get old and lose your interest in programming (or whatever else you're using ping for) while waiting for the goddamn thing to finish!

To try and solve this problem let's add a deadline flag to the ping command that specifies how many seconds we should wait for reply:

while IFS= read -r line; do

ping $line -c 1 -w 1

done < hosts.txt

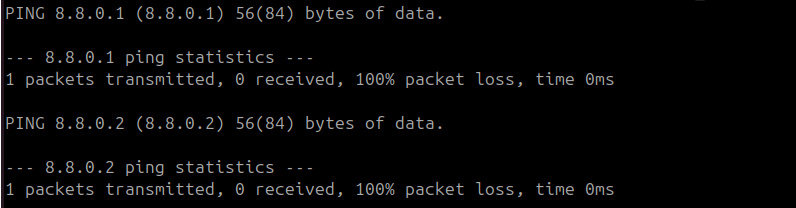

Notice '-w 1' part on the second line? This tells ping that if no reply for 1 second - drop it and let us move on to the next patient on the list. The outcome of this modification is the same as shown on the screenshot above, only difference being that we're waiting for 1 second instead of 10 seconds for every non-replying address. Therefore, in our little example of 3000 hosts being offline, we'll waste 3000 seconds for waiting. That's 90% improvement from our previous figure of 30000 seconds, but still long enough to mess up your coffee and make your beer taste like donkey piss.

Let's summarise some of the problems one might face when using a default ping on a range of IP addresses.

Disadvantages when using standard ping utility for the whole subnet

1) Ping requests will be sent in a non-parallel (synchronous) manner causing significant delays.

Let's have a look at the script above. For every host that we ping we'll have to wait for reply or a timeout before we can move on to the next one. This becomes a major problem when we're pinging big number hosts. Just look at the figures of 30000 seconds or even 3000 seconds mentioned in our example.

Wouldn't it be nice to be able to ping the next host while we still waiting for reply from the previous one? Do it asynchronously, or in parallel? Instead of blocking the execution for 1 second (or 10 seconds in case of default timeout) and waiting for a miracle, we can send countless ping requests within that time frame. Simply put: we can send a bunch of requests at once, and then wait for a bunch of replies or non-replies. All in parallel.

2) Ping won't accept subnet and mask as an argument.

Let's pretend we need to ping the following subnet: 8.8.0.0/20. How do we feed this expression to ping? It's a good utility, but way too dumb to understand these things. You'll have to generate the list of hosts by yourself, either by:

- jumping online and finding some crappy website that will do it for you,

- or by writing the goddamn generator yourself like I did (sigh)

Sounds like a lot of work, right?

I'm sick of reading this crap. What is the point of this article?

Due to reasons stated above, and also because I enjoy reinventing the wheel, I decided to resurrect my old uni project mostly written by my mate and take credits for it fill this horrible gap in Linux software with my brand new utility called ping_subnet. It's capable of all the good things we talked about, and in the following chapters of this edge-of-your-seat saga I will walk you through how it works, what's inside and what is so magical about it. And of course there will be a lot of POSIX sockets like I promised you earlier.

Stay tilted tuned for more ping_subnet.